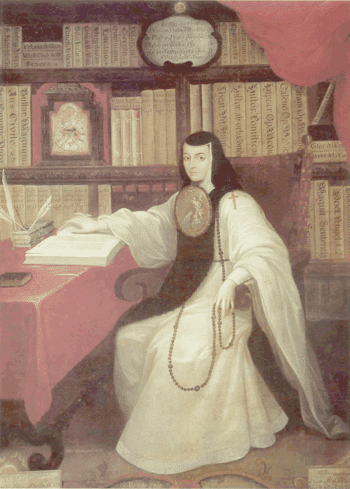

Born in New Spain (now Mexico) in 1651, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a nun who wrote what is considered the first feminist manifesto. She was revered as a prodigy during her lifetime, and was one of the most widely published writers of the period.

The illegitimate child of a creole woman and a Spanish captain, Juana came from a poor family. She was raised in the country in the home of her mother’s father.

At the age of three, Juana followed her sister to a girls’ school and begged to be taught to read. She soon began devouring the books of the grandfather’s library, reading everything she could get her hands on.

Juana had an insatiable appetite for knowledge, and all the books in her grandfather’s hacienda were not enough. She asked her mother to be allowed to go to the university in Mexico City disguised as a boy, but her mother unsurprisingly didn’t think that was a good idea. However, she did consent to send Juana to Mexico City to study under a scholarly priest.

In Mexico City, Juana became fluent in Latin after only 20 lessons, and began to write poetry in Latin, Spanish, and some in Nahuatl (an Aztec language). She punished herself for not learning fast enough by cutting her hair short if she didn’t meet her own deadlines.

Juana became known in court as a child prodigy. The viceroy of New Spain, the Marquis de Mancera, was impressed by her knowledge, and tested her with a barrage of learned men, theologians, philosophers, mathematicians, historians, poets, and other specialists. During this time at court she continued writing poems and sonnets. The Marquis’ wife, impressed by Juana’s intellect, chose Juana to serve as her handmaiden.

At the age of 20, Juana entered the Convent of the Order of St. Jerome and took her vows as a nun. In the convent, she had her own study and library, and the freedom to meet with men of learning from the Court and University. She wrote many poems and plays, was skilled at music and music theory, and studied all branches of knowledge including philosophy and natural science.

Thought she doubtless had suitors during her time at court, Juana had no interest in marriage: “I took the veil because […] it would, given my absolute unwillingness to enter into marriage, be the least unfitting and the most decent state I could choose.”

Juana had the freedom to study and write in the convent because of the protection of benefactors such as the Viceroy and his wife. Always under a barrage of attacks against her “unfeminine” thirst for knowledge, Juana considered her own intellect a mixed blessing:

“I thought I was fleeing myself, but — woe is me! — I brought myself with me, and brought my greatest enemy in my inclination to study, which I know not whether to take as a Heaven-sent favor or as a punishment.”

In 1688, her current benefactors, the Marquis and Marquise de la Laguna, departed for Spain, leaving Sor Juana to face her criticizers alone. Chief among them is the Archbishop of Mexico, who was fiercely misogynistic and strongly opposed to secular drama such as Juana wrote.

The famous “feminist manifesto” Sor Juana wrote was a response to criticisms from a supposed friend. In 1690, Juana had, in confidence, given a written critique of a famous sermon to a Bishop, who then turned around and published it without her permission. Along with Juana’s critique, the Bishop included a pseudonymous letter of his own admonishing her for her intellectual pursuits. (“Letters engendering pride in women are not pleasing to God.” “You have wasted much time in the study of philosophers and poets.”)

Sor Juana responded with her famous letter simply named “Respuesta” (meaning “reply” or “response”), which passionately and cleverly defended her thirst for learning. In the letter, she recounts her intellectual history, and defends her own and all women’s right to education.

“Who has forbidden women to engage in private and individual studies? Have they not a rational soul as men do?…I have this inclination to study and if it is evil I am not the one who formed me thus – I was born with it and with it I shall die.”

Towards the end of Sor Juana’s life (as it happens with so many women in history), the details are scarce. What we do know is that in 1692-93, Mexico City saw flooding, disease, and food riots which weakened the power of the court. In 1693 there was an ecclesiastical investigation that involved Juana. In 1694, the same year of her 25th anniversary as a nun, Juana signed affirmations stating that she planned to donate of all her books, maps and instruments to be sold to help the poor.

It’s unknown whether she did so of her own volition or under duress, but even if it was her own choice, it was an understandable capitulation to the pressures and criticisms she had endured her entire life.

Only a year later, Sor Juana succumbed to a plague after caring for her sick sisters.

“I went on with my studious task of reading and still more reading, study and still more study, with no teacher besides my books themselves. What a hardship it is to learn from these lifeless letters, deprived of the sound of a teacher’s voice and explanations; yet I suffered all these trials most gladly for the love of learning.”

Next, read about Ketair Tekakwitha: The Making of a Mohawk Saint, or Lady Mary Montagu, Brilliant Autodidact Aristocrat!

Image of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Keri is a blogger and digital marketing professional who founded Amazing Women In History in 2011.

Wow! You go girl! If I thought it was rough to speak my mind in today’s world then I’ve been too long away from chronicles such as this. It is no surprise to me that she chose to be a nun. No woman could have pursued academia without the permission and protection of a rich father, which she did not have, or the highest and almighty father, God. And even then the damn bishops got in her way. Why oh why do men fear our power so? It’s been the all telling and never faltering confirmation that we’ve always been powerful beyond belief. Why else would people work so hard to suppress us?

Thanks for your comment! I totally agree. I try to keep the tone on this blog neutral, but I was so angry and saddened especially reading about the last few years of her life. I just imagine all the pressure she was under her entire life, being consumed by this unquenchable fiery passion to learn more and more, and being shot down on all sides. Who knows what else she would have accomplished if she had had as much freedom as 17th century men like John Milton or Isaac Newton. Her name should be just as famous as theirs. Reading her writing (even translated) makes me feel such a connection to her.

Congratulations for you blog and rescue the name of so wonderful women in the history!

I always have thought that Sor Juana was a woman in a wrong time. She was ahead of her time.

There is a book in spanish written by M. Lopez Portillo where the author talks about the early years of Juana. It is amazing to see how she was so enthusiastic about knowledge. As you said, with different conditions, I am sure that she could have the opportunity to do more than poetry.

Great site and biography! As a historian focusing on Latin America, I learned about her in graduate school, but had to revise the interpretation that she became a religious because of a failed romance. When one reads her “Foolish Men,” and learns more, her motivations could not have been clearer. I will be teaching a course at Sonoma State Osher Lifelong Learning Institute in January, 2017 entitled Compañeras, From La Malinche to Evita, Women of Latin America, which will include Sor Juana and many more extraordinary women in Latin America: Inés Suárez, Sor Juana, Catalina de Erauso, Manuela Saenz, Gabriela Mistral, Evita, Frida, Tina Modotti, etc.

I watched the Netflix miniseries “Juana Inez,” and fell in love with her portrail.

Thanks for sharing. She definitely was a kick-ass woman. She is my second cousin separated by 10 generations. I am currently researching and writing a book about the family’s genealogy. I am very proud of her and her contributions to latin american literature. I can say this, she didn’t enter the convent because she felt compelled to a religious life. She went in for the reason of being able to have access to books and be able to continue to learn. Had she married she would not have the kind of freedom she had as a nun. Francisco de Aguiar y Seija got on her for a few reasons, one he did not feel she was devoted to her religious occupation nor took it seriously, and her very secular nature of writing which to him wasn’t appropriate for a nun. This man was literally a zealot but did some good things like open schools for the poor and so forth. But anyway he believed that nuns should know their place and yes he was definitely misogynistic and avoided women. It unfortunately was the mentality for that time. I definitely believe that she was heavily pressured to give up her library especially by this man and his connections to the inquisition. She walked a very fine line with it. Juana Ines had two nieces one was from the daughter of her sister Maria de Asbaje named Sor Maria de San Jose who also was in the San Geronimo convent and another niece known as Sor Feliciana de San Nicolas from her half sister Ines, yes Ines is a family name I found out. There was like a total of 5 with that name in the family I found. Named after Ines de Brenes the matriarch of the family. There were many family members that entered into the church both as priests and nuns. The show was ok, it definitely wasn’t a very accurate portrayal of her but it certainly brings awareness and an interest of her. The more I learned about this relative of mine the more I came to admire her. Her love for learning and her ideals. She truly was a head of her time.

She was a nun. She died as a nun. Why not show her as a nun, there are images available. Or is the habit “non-feminist”?

You’ve got a good point. There wasn’t any particular reason I chose that image except that it was one I liked 🙂

Personally I think most organized religions, especially Catholicism and Christianity, are extremely patriarchal, anti-women, and anti-feminist. But at that time, it was the only option for many women to escape the slavery of being sold into marriage, and actually receive an education.