“Valérie André is one of the great military aviators of the twentieth century. She was the first woman to fly a helicopter in combat and one of the first three helicopter medevac pilots. Flying more than 150 helicopter rescue missions during the French war in Indochina (including at Dien Bien Phu), and parachuting into the field twice, André was a trailblazer, a pioneer of flying helicopters in combat and an innovator of battlefield medicine, who risked her life to treat the wounded, whether they were French or Vietnamese, whether they were friend, civilian, or foe. Aviation historian Charles Morgan Evans tells her story with verve and pathos.”

Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt chapter from Helicopter Heroine: Valérie André—Surgeon, Pioneer Rescue Pilot, and Her Courage Under Fire by Charles Morgan Evans.

Near Nam Dinh, Northern Vietnam, November 16, 1952

The heat inside the fishbowl cockpit was unbearable, but the pilot—her left hand firmly grasping an overhead control stick—paid little attention to it. Her focus was on her mission and keeping her cantankerous Hiller helicopter airborne.

Her destination was one of the small French army outposts concentrated along the Red River just past Nam Dinh. A young Vietnamese soldier with a critical head wound needed immediate transport back to Hanoi. With minutes to go before landing, she radioed into air traffic control in Hanoi to report her position. She noted that her fighter escorts had not yet made contact.

At least the Viet Minh don’t have antiaircraft guns, she thought to herself. Yet.

The sky over Tonkin was clear and blue, giving little clue to the war taking place two thousand feet below. But on the ground, the pilot and her machine were vulnerable targets, and she fully realized the danger she was flying into. Her pulse quickened as she spotted her landmark by the river. The outpost was just ahead.

Long days and dangerous missions were not new experiences for this pilot. She had been in Vietnam for five years, serving as a surgeon in military hospitals. For five years, the pilot’s survival had depended on constant vigilance, quick reflexes, intelligence—and luck. She did not wish to push that luck and looked again for her escorts.

To her relief, the fighter pilots arrived and performed a flyby past her slower-moving helicopter. She admired the fighter pilots and envied the speed of their aircraft She could always count on the Viet Minh hiding in the thick vegetation to follow every move she made and to fire on her whenever they could. That was why the fighter planes were called into action and sent into the area before the unarmed helicopter would land. The escorting fighter pilots knew what she expected of them.

They came in at high speed and low altitude, laying down a merciless pattern of machine-gun fire that struck deep into the thick vegetation surrounding the outpost. Today it was only a strafing run. On other missions, it might be necessary to drop napalm. Their barrage only lasted a minute or so, but it was enough to keep the enemy at bay. With their work finished, the fighters split off to head back to Hanoi.

She had already transported four other wounded men to Hanoi that day, and fatigue was setting in. Below was the landing zone, crudely marked out with linen sheets and scraps of wood secured by stakes and stones to the ground. Evacuations at remote outposts were always carried out quickly to avoid cutting power to the engine. It wasn’t always a sure bet that the Hiller’s engine would start again after a complete shutdown. One thing was sure, however. The Viet Minh would soon regroup.

The helicopter’s rotor blades slowed as the engine wound down to an idle. The men from the outpost knew not to move until the aircraft was on the ground. The pilot stepped out from the cockpit as a field medic and two other soldiers approached in a crouching run bearing the wounded man on a stretcher.

“Bullet in the head,” the medic shouted to her above the din of the engine and still swishing rotors. “He’s in a coma and been stuffed with Sedol.”

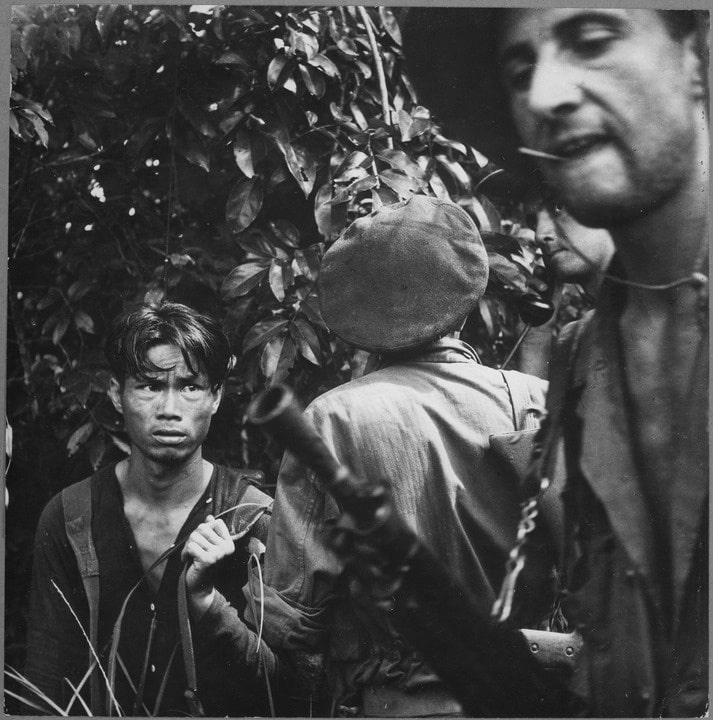

The wounded man’s face was ashen. The medics had wrapped the top of his head in linen gauze. The bandage was already blood-soaked, and his wound continued to seep. She looked the patient over carefully. He was probably not even twenty. He was one of many Vietnamese now fighting alongside the French against other Vietnamese. This soldier was smaller than a typical Frenchman but somewhat stocky with broad shoulders.

“Could you tie up his hands?” she asked. “I would prefer it.”

The pilot knew all too well from experience never to underestimate what could happen while moving a wounded patient by air—even one as severely injured as this young Vietnamese soldier. The medic nodded to one of the men bearing the stretcher, and he produced a small length of cord.

With the comatose soldier’s hands now secured, they began moving the patient toward one of the side-mounted stretchers attached to the helicopter. No one could shake the sense that enemy eyes and weapons were trained on them. They were all targets and the threat of weapons fire erupting at any moment was very real.

Once the soldiers had positioned the patient beneath the Plexiglas fairing enclosing the helicopter’s stretcher, the pilot twisted the throttle to rev the helicopter’s engine for liftoff. Hanoi was less than a half hour away at full power, but the helicopter’s engine always labored in the sweltering tropical atmosphere.

Finally, the Hiller achieved a relatively safe altitude and pushed along at its normal cruising speed of seventy miles per hour. She retraced her flight along the banks of the Red River leading back to Hanoi. The pilot exhaled deeply, flexed her hands, and stretched a bit to release the tension in her neck and shoulders.

But her relief was short-lived. She glanced back at her patient and saw to her horror that he was regaining consciousness.

Merde, she thought. Not enough Sedol!

The soldier awoke in wild spasms, terrified at finding himself in the air. Looking down, the pilot could see the primal fear in his eyes. Alarmed, she watched as the man clenched his jaw and fought his restraints, summoning almost supernatural strength to retake his freedom despite being more than a thousand feet above the ground.

She could see that the patient had slipped free of his restraints and that he was struggling to reach into the cockpit. His desperate hands thrust inside the cabin, grabbing at the helicopter’s floor-mounted foot controls. The pilot’s attempts to calm the soldier went unheard as he clutched and clawed at her feet. The aircraft pitched wildly, perilously out of control, as she fought the crazed soldier and wrestled with the Hiller.

It was a nightmare scenario. She coolly reviewed her choices as she fought for her life and his. She could have immobilized him with a kick, but that would probably have killed him. Not an option for a doctor who had taken the Hippocratic oath. And so she desperately battled with her feet, trying to push the frantic soldier away from the controls and back into his litter.

His clutching at the foot controls could easily have caused the Hiller to spin, disorienting the pilot and leading to a lethal crash. Had he succeeded in jarring her arm and triggering a “mast bump,” a loss of control, the helicopter would likely have plummeted. And so she fought for time, for the minutes it would take to get them to safety.

Her efforts paid off. As suddenly as the man had risen from his catatonic state, his face froze, his body stiffened, and he went limp. He fell back into his coma and mercifully into a deep sleep. Breathing heavily and with great effort, she brought the helicopter back under control. Her body, jolted by adrenaline, vibrated like a tuning fork. Minutes later, they made it to the outskirts of Hanoi, not far from the landing zone at Lannesan Hospital.

Gently placing the helicopter onto the immaculately groomed hospital landing zone, the pilot was met by medics who offloaded the young Vietnamese soldier and rushed him inside for surgery. She would later learn that the young man had survived. With her mission complete, she was able to shut the helicopter down. Her khaki coveralls were drenched in sweat, and she noticed the soldier had undone her bootlaces.

Leaning against the side of her helicopter, she slowly lowered herself to the ground while pulling a cigarette and a lighter from her pockets. She stared blankly ahead as she dragged deeply and exhaled a long stream of smoke. For a short moment, she could relax.

It had been a punishing day. This was no place for a woman.

***

Charles Morgan Evans lives in Reno, Nevada and is also the author of The War of the Aeronauts—A History of Ballooning During the Civil War (Stackpole Books, 2002). He is the founding curator of the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, California.

Evans first learned of Valerie Andre’s story at the Hiller Museum. She flew Hiller 360 helicopters in Vietnam, alongside her future husband, Alexis Santini, France’s first military helicopter rescue pilot. From 1951 to 1953, Valerie Andre flew 128 rescue missions, rescuing 168 wounded soldiers in some of the most hazardous combat zones in Vietnam. Valerie later served in Algeria as a medical rescue pilot, and during the 1960s became an advocate for including more women in the French military medical corps. In 1976, Valerie Andre became the first woman promoted to the rank of general in the French Army.

Valerie Andre celebrated her 102nd birthday on April 21, 2024

Charles M. Evans is the founding curator of the Hiller Air Museum in Redwood City, California. He has written about aviation history for such publications as American History, Aviation, and Civil War Times Illustrated and is author of War of the Aeronauts: A History of Ballooning in the Civil War (Stackpole, 2002).

Leave a Reply