Women have made contributions to science throughout history, despite facing a variety of challenges due to their gender. One such challenge, which affects the acknowledgment of women’s scientific achievements, is called the Matilda Effect. In order to fully appreciate the accomplishments of women in science and the barriers they have faced, it’s important to understand what the Matilda Effect is and how it has affected women in science.

What is the Matilda Effect?

The Matilda Effect is a phenomenon where the work of women scientists is downplayed, ignored, overlooked, or attributed to men. The Matilda Effect makes it more difficult to see the contributions women have made to science throughout history, and contributes to the belief that women are not as naturally predisposed to science as men.

The Matilda Effect isn’t just about stealing credit. It can manifest in several ways:

- Downplaying Achievements: A woman’s work might be considered less significant or groundbreaking than a man’s even if it’s equally impressive.

- Lack of Recognition: Women may be passed over for awards, promotions, or opportunities to present their research.

- Citation Bias: Studies by women may be cited less often than those by men, even in similar fields. This can make their work seem less impactful.

The Matilda Effect discourages women from pursuing careers in science. It also creates a skewed perception of scientific history, where women’s contributions are minimized.

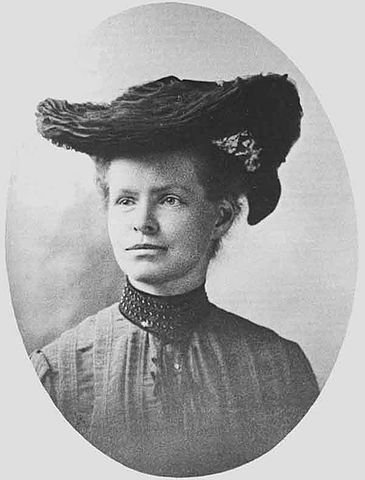

Who is the Matilda Effect named for?

The Matilda Effect is named after the abolitionist, suffragist, and science writer Matilda Joslyn Gage. Gage brought many previously unacknowledged accomplishments of women to light in her popular books and pamphlets.

Margaret W. Rossiter, a science historian, first named the effect in a 1993 paper called “The Matthew Matilda Effect in Science.” She confirmed through an analysis of over a thousand scientific papers that the work of men is cited more often than the work of women, taking into account the proportion of work by gender.

Matilda Effect Examples

The Matilda Effect, though not named until very recently, has been recorded as affecting women in science since at least medieval times. Trotula de Ruggiero is an early example: her writings on medicine and gynecology in the 11th and 12th centuries were often attributed to men since it was believed that a woman would be incapable of such work.

One of the most famous cases of the Matilda Effect is the work of Rosalind Franklin. Rosalind Franklin was a British scientist who made crucial contributions to our understanding of the molecular structures of DNA and RNA. Her work on the X-ray diffraction images of DNA was key to the discovery of the DNA double helix, but her role in the discovery went unacknowledged until decades after her death. The credit went instead to her fellow researchers Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, who used much of her work without permission or acknowledgment. Crick, Watson, and Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962, while Rosalind Franklin was never nominated.

Nettie Stevens, who discovered sex chromosomes, is another example. E. B. Wilson, Stevens’ colleague, has been cited commonly as the person who discovered the sex chromosome, and sexism is the only logical explanation why this is the case.

Other examples are Lise Meitner, whose work in nuclear physics was credited to Nobel Prize winner Otto Hahn in 1944, and Chien-Shiung Wu, a Chinese American physicist called the “First Lady of Physics,” whose work in the discovery of parity violation went uncredited while her colleagues Lee and Yang were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1957.

The scientific accomplishments of women have often gone unrecognized and ignored due to the Matilda Effect. Thanks to the naming and acknowledgement of such phenomena, more women scientists are being recognized today for their pivotal roles in the advancement of science.

Recognizing the Matilda Effect is a first step. Actively promoting the work of female scientists, ensuring fairness in awarding recognition, and encouraging mentorship for women in STEM fields can all help counteract this bias.

Keri is a blogger and digital marketing professional who founded Amazing Women In History in 2011.

Leave a Reply