At the start of the 20th century, a female biologist was working to solve a scientific problem that had troubled humanity for ages. The problem was simple but daunting and it touched on how men become male and how women become female. Through her research work, biologist Stevens discovered that chromosomes are responsible for the sex of individuals, animals and every other living organism.

Before Stevens’ discovery, people were clueless about how people acquired their biological sex.

Thanks to the research work of dedicated biologists Stevens – and the work built on it afterward – we now understand that the biological sex of an individual is hereditary. We also know that it’s the chromosome in the dad’s sperm that is responsible for the sex of the offspring.

But before this discovery, this issue was largely a mystery and the theories around it were interesting as well. Renowned scientist Aristotle believed that the sex of a child was determined by the father’s body temperature when having coitus. He even went ahead to advise dads to have sex during summer if they wanted male offspring.

Another interesting theory making rounds during that time implied that nutrition determined the sex of a child. The same theory went ahead to say that parents that had poor nutrition gave birth to male children and those that fed well sired females. I don’t even want to imagine the things parents that desired male children had to do according to this theory.

But after Stevens’ discovery, we have learned that all this was nonsense.

The experiment that led to sex determination

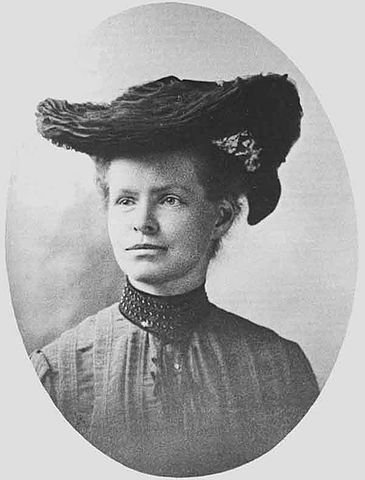

Born in 1861 in Vermont, Nettie Stevens was passionate about science from an early age. She worked as a teacher after graduating high school but at the back of her mind she knew that was not what she was destined to do.

She saved money from her teaching profession and enrolled into Stanford University at the age of 35 to do what she always dreamt of doing which is to study science. She excelled as a science student and graduated top of her class with a B.A in 1899. She did her M.A a year later

She then joined Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania and it is here where she worked to solve the problem of sex determination. The theory that chromosomes bore hereditary information was relatively new in early 1900 and the science world was trying to determine how character traits like the biological sex of an individual were passed down across generations.

Stevens was working on the mealworm beetle as she sought to find out if sex was genetically inherited. When observing the female mealworm beetle, she found that her sex cells had 20 large chromosomes. The male also had 20 chromosomes but only 19 were large and the 20th was small.

She wrote in a report that that distinct feature was a clear case of sexual determination.

She concluded that the difference in either male or female offspring was down to the sperm of the male beetle. If the sperm contained the smaller 20th chromosome, then the offspring would be male and if the sperm contained the large chromosome, the offspring would be female. She didn’t name the chromosomes X and Y chromosomes. (This naming convention would be adopted at a later date.)

Nettie Stevens did not get credit for her work – initially

E. B. Wilson, Stevens’ colleague and legendary biologist has been cited commonly as the person who discovered the sex chromosome, and sexism is the only logical explanation why this is the case.

Wilson was researching on the same issue as Stevens and they published their research findings at about the same time. Wilson’s research was based on the fact that females have one more chromosome than males but Nettie Stevens’ findings of different chromosomal identification (X and Y chromosomes) is more accurate and supports Mendel’s genetics theory that states that some genes are more dominant than others.

In fact, Wilson did not arrive at his research findings until after he had accessed Stevens research. But since he was a more established scholar by that time, he is commonly cited as the individual who discovered sex chromosomes.

Gone too soon

Nettie Stevens started her career in science very late and it was quite unfortunate that it ended early as well. After her discovery on sex chromosomes, Stevens continued her research work at Bryn Mawr College and received her Ph.D. in 1905. She worked as an assistant professor at the college until her death in 1912.

Breast cancer was what caused her death and it is quite unfortunate that it robbed the world of a distinguished research fellow who made the biggest discovery in the world of genetics.

In her brief period as a scientist, Stevens achieved a lot more than her peers who had longer careers.

Next, read about Stephanie Kwolek, inventor of Kevlar, or Top 5 Brilliant Patented Inventions by Women!

Nice article, but you should check the dates. It says she was born in 1961 and received her BA in 1989.

Thanks for catching those typos Julie – just fixed 🙂