Mary Richards was born into slavery in Richmond, Virginia. Freed by the Van Lew family who owned her, she was sent to school in the North, in order to become a missionary. At age 15, she was sent to teach in Liberia, West Africa. But after four years, ill and miserable, she wrote to her patron Elizabeth Van Lew, demanding to be brought back to Richmond.

Having lived in freedom since childhood, she found it impossible to settle down in the repressive conditions of slave-owning Virginia. Within months, she had been arrested for going about without the pass that all black people were legally required to carry.

The wealthy and influential Van Lew family had to bail her out. Shortly afterwards, she married Wilson Bowser, another freed servant of the Van Lews. The day after her wedding, Virginia broke away from the United States, and joined the rebel side in the Civil War.

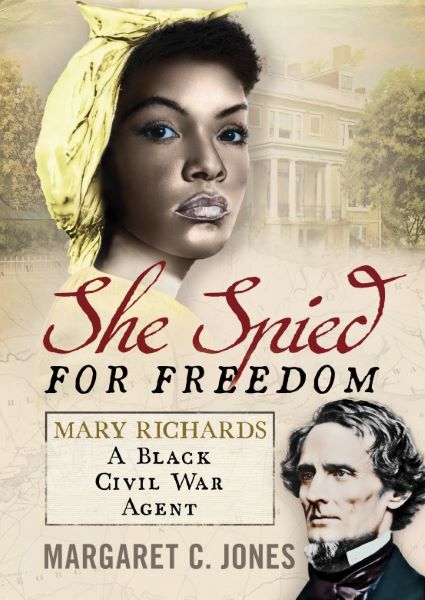

Passionately opposed to slavery, Mary hoped that a victory for the Union in the war could put an end to slavery once and for all. The chance to play her part in the war effort came when – probably with the help of Elizabeth Van Lew, who had established a formidable spy network in Richmond – Mary went to work in the home of the rebel Confederate President, Jefferson Davis.

Posing as an illiterate slave. she would have had access to classified documents in Davis’ study, and to those he carelessly left lying around outside. She might overhear conversations in the dining room where Davis invited his generals to discuss wartime strategy. As a fellow agent later described her work, “Mary was the best, as she was working right in Davis’ house.”

He recalled how she once discovered and passed on a set of Confederate proposals for a final peace treaty with the Union. Van Lew’s agents publicised this information, to the fury of the the Confederate government.

It was dangerous work, especially for a black person. One of Mary’s fellow agents, a free black man named William Roane, was arrested off the street, and never seen again.

After the war, Mary was involved in teaching former slaves, helping to start up schools in Virginia and Florida. Then a school she founded in St Marys, Georgia, came under threat from the newly-formed Ku Klux Klan. Mary had no illusions about the danger: “These secret societies are doing something at least trying to do something.”

Experienced in studying human behaviour, she noted on some white faces “the quiet but bitterly expressed feeling, that I know portends evil”. Attacks on black officials, and intimidation of teachers were becoming commonplace. Then, a doctor friend who, like Mary, worked with the black community, received a death threat. Besides, though her pupils were learning well, Mary’s school was struggling financially. Her employers, the Freedmen’s Bureau, decided to close it. Soon, violence by vigilante gangs would make most of the Bureau’s work impossible.

Unable to find new teaching work, Mary left the South for New York. From there, under the name of Mary Denman (she had briefly married twice while living in Georgia), she wrote to her patron Elizabeth Van Lew. She was supporting herself as a seamstress, while hoping later to attend teacher-training college – if only the chronic fever that had dogged her from her time in Liberia would allow her to go on in the work she loved. Elizabeth wanted Mary to go back to Richmond and live with her – but Mary proudly asserted her independence. A mature woman of 30 now, she would continue to make her own way in the world.

After this letter, Mary Richards disappears from history, only to resurface in our time as the subject of umpteen, largely inaccurate, myths and legends. Inducted into the US Military Intelligence Hall of Fame, even there, they get her name wrong, calling her “Mary Bowser”. But their tribute is clear enough: “She was one of the highest placed and most productive espionage agents of the Civil War… [Her information] greatly enhanced the Union’s conduct of the war.”

Mary Richards’ grave site is unknown; but her admirers have placed a memorial stone in Richmond’s Woodland Cemetery. The inscription on it reads:

SHE RISKED HER LIFE AND LIBERTY SO THAT ALL COULD KNOW FREEDOM

Recommended Reading

Leave a Reply