In November 1861, while she was staying at Willard’s Hotel in embattled Washington, DC, Julia Ward Howe wrote the lyrics to the most famous patriotic anthem of the Civil War. “It would be impossible for me to say,” she wrote in her Reminiscences (1899), “how many times I have been called upon to rehearse the circumstances under which I wrote the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic.’ ”

Indeed, until she died in 1910 at the age of ninety-one, Howe endlessly told and retold the story of how she had come to write the lines that made her famous. Everywhere she traveled or spoke—at a school in St. Paul, a Unitarian church in Chicago, a gathering of black women in New Orleans, or a flower-bedecked Memorial Day celebration in San Francisco—she was expected to read the words of the song, or sing them in her trained contralto; and choruses and soloists around the world enthusiastically honored her by performing it as well. This “oft-told tale,” she noted, had become for many Americans the story of her life.

A century ago, the first biography of Howe, written by three of her daughters, and published in March 1916, just six years after her death, won the Pulitzer Prize. Awarded for the first time in 1917, in the midst of another war, the Pulitzer Prize had a strong moral and nationalistic purpose. Nicholas Butler, the president of Columbia University and the administrator of the awards, called Julia Ward Howe the “best American biography teaching patriotic and unselfish services to the people, illustrated by an eminent example.”

Despite this sanctimonious encomium, the two-volume biography was not as didactic as Butler’s tribute makes it sound. The daughters drew on the Howe family correspondence, plus Julia’s essays, poems, memoir, and journals, to tell a lively story of a woman as charming and funny as she was learned and thoughtful, as devoted to her large family as to public service. Howe was certainly eminent, unselfish, and patriotic. She had six children, learned six languages, published six books; she was a prominent figure in the churches and intellectual societies of Boston; she joined ardently with her husband in the abolitionist struggle; she traveled all over the United States, the Caribbean, and Cuba, and abroad to England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Greece, Cyprus, Palestine, and Egypt; she founded and led the Association of American Women, served as president for the New England Woman’s Club, the New England Suffrage Association, and the American Woman’s Suffrage Association. Howe was the first woman to be inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Born three days after Queen Victoria, she was sometimes called the Queen of America.

The daughters also wrote an inspiring story of their parents’ marriage. When she married Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, Julia Ward was an aspiring poet, a beautiful, accomplished, studious heiress known in New York social circles as “the Diva.” Samuel G. Howe, eighteen years her senior, was a hero of the Greek Revolution of the 1820s and a world-famous doctor who had developed a method for educating blind children; his name, the critic John Jay Chapman noted, “was known to everyone in the civilized world.”

Together the Howes were one of the leading power couples of nineteenth-century America, uniting exceptional intelligence, moral fervor, worldly ambition, immense energy, and public commitment. Living in Boston, they knew many of the key literary, political, intellectual, and scientific figures in the Civil War era, including Charles Sumner, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Margaret Fuller, and John Brown. They traveled to Europe on steamers as often as modern jet-setters would amass frequent-flyer miles and made friends there as well; Florence Nightingale was the godmother of one of their daughters; Dickens, their guide in London. They were devoted and imaginative parents, and their marriage, in the title of another memoir by their daughter Laura E. Richards, was the fusion of “two noble lives.”

But that first biography hid as much as it revealed. In reality, the marriage was turbulent and unstable—a prolonged domestic battle over sex, money, independence, politics, and power. The Howes disagreed, quarreled, separated, often lived and worked apart. Despite his inexhaustible compassion for the suffering, helpless, and deprived, and regardless of his dedication to the abolition of slavery, Howe held obstinate and conservative views on women’s roles in public life. He expected his wife to be completely fulfilled in her domestic and maternal role, and to accept with gratitude his right to make all the decisions about their lives together. A towering figure in the field of philanthropy and social reform, at home he was dictatorial, restless, and touchy about his own authority, “an ordinary man,” as Chapman wrote, “a man of headaches and irritability, a man of doubts and errors.”

Julia Ward expected to have a partner who would introduce her to his more consequential world of ideas and social reform, and allow her to act in it. She assumed that she would be an equal partner in their decisions and free to develop and pursue her own literary aspirations. She hoped to “write the novel or play of the age.”

Her husband, however, tried to stop her writing after she published an anonymous book of confessional poems that enraged and humiliated him. He took control of her large fortune, and lost most of it. Throughout most of their marriage, famous and beloved though Julia became, his expectations dominated hers. She had to exercise her power obliquely with the soft feminine weapons of tears, self-sacrifice, unselfishness, domesticity, and maternity. For personal self-expression and public communication, she had to use the conventional medium of lyric poetry, and then even that was eventually denied to her.

Nevertheless, in the course of their marriage, she learned how to resist his dictatorship, respect her own needs, and develop, defend, and act upon her convictions—in sum, how to think about the manifold ways that the politics of inequality entered the household.

Writing the “Battle Hymn” was the turning point in her life, and its renown gave her the power and the incentive to emancipate herself. The Civil War challenged nineteenth-century ideals of separate spheres for men and women, changed assumptions about gender, and propelled women out of domestic confinement into public lives and careers. In Howe’s case, this transformation was also a rebellion against her marriage. She fought a second civil war at home, battling with her husband over her rights to independence, equality, and a public voice.

After her husband’s death in 1876, Julia was free to forge a new identity. For the second half of her life, she was a leader of the fight for women’s suffrage. She traveled alone or with other suffragists all over the United States campaigning for women’s rights. She became an advocate for the emancipation of the silenced and subjected.

Although her children, and then her grandchildren, continued to complain about her extra-domestic activities and attempt to thwart them, Julia insisted on doing what she believed necessary and right. The glorious final decades of her life were a result of the limitations of her marriage and a refutation of its confining bonds.

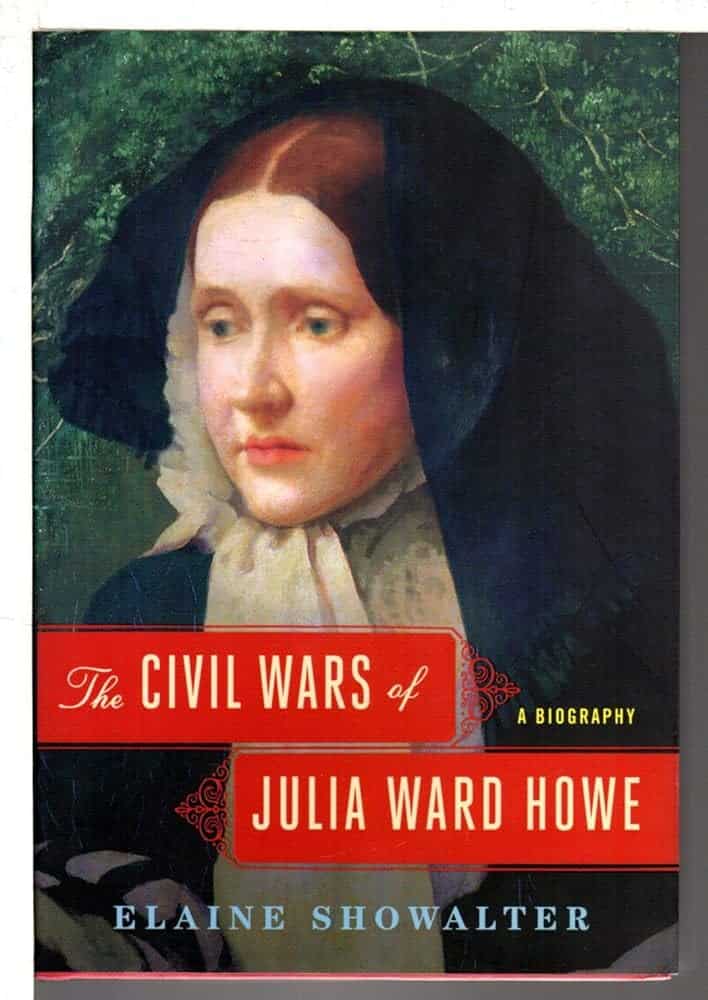

There have been a few excellent biographies since 1916, but there is none that looks at Julia Ward Howe as a major American heroine and sees the marriage of the Howes as a paradigmatic clash of nineteenth-century male and female ambitions. The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe tells the story of her battle in that other civil war of emancipation.

For those intrigued by the untold story of Julia Ward Howe’s role in the Civil War and her personal struggles, consider delving deeper into her narrative with an insightful ebook that explores the complexities of her life and legacy, shedding light on her contributions as a pivotal figure in American history.

Recommended Reading

This post is an excerpt from Elaine Showalter’s book The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe, which “tells the story of Howe’s determined self-creation and brings to life the society she inhabited and the obstacles she overcame.”

Elaine Showalter is an American literary critic, feminist, and writer on cultural and social issues, and the author of The Civil Wars of Julia Ward Howe: A Biography.

Leave a Reply